When Anna Estcourt was twenty-five, and had begun to wonder whether the pleasure extractable from life at all counterbalanced the bother of it, a wonderful thing happened.

So begins The Benefactress by Elizabeth von Arnim, another of her fairy tale stories in the same vein as Christopher and Columbus and The Princess Priscilla’s Fortnight (not to mention The Enchanted April, which everyone else seems to adore but is my least favourite von Arnim). It is one of her earlier novels – first published in 1901 – and, as in the two books that came before it (Elizabeth and Her German Garden and The Solitary Summer), von Arnim clearly drew on her own experiences for inspiration. And isn’t it any writer’s prerogative to write about what they know, especially if they can do it over and over again so delightfully? In von Arnim’s case, that was the plight of the well-born foreigner living in rural obscurity in Germany.

Anna Estcourt, pretty, bright and still unmarried at twenty-five, has grown up under the guardianship of her benignly disinterested elder brother and his bossy, social climbing wife, Susie. With no money – and therefore no independence – of her own, Anna is like a child under Susie’s thumb (and is far meeker at times than Susie’s own daughter). Susie cannot understand why Anna will not make the most of her good looks and good name to catch a wealthy husband. But Anna, a rather dreamy, idealistic soul, refuses to compromise her ideals just to get away from Susie:

‘…isn’t it simply terrible to be expected to encourage any wretched man who has money? I don’t want anybody to marry me. I don’t want to buy my independence that way. Besides, it isn’t really independence.’

When Anna’s Uncle Joachim, her German mother’s brother, comes to visit, he and Anna immediately strike up an affectionate friendship. Neither can entirely understand the views of the other – Uncle Joachim believes “It is a woman’s pride to lean on a good husband. It is her happiness to be shielded and protected by him” – but nonetheless he, having met the exhausting Susie, can understand Anna’s desire for independence from her. And so, when he dies a few a months after his visit to London, Anna finds herself an heiress, the inheritor of his prosperous Pomeranian estate, with the instruction that Uncle Joachim

trusted his dear Anna would go and live there, and keep it up to its present state of excellence, and would finally marry a good German gentleman, of whom there were many, and return in this way altogether to the country of her forefathers.

Anna has no intention of marry a good gentleman – German or otherwise – now that she has a generous annual income to fund the independent life she has dreamed of for so long, or of living in rural obscurity in Northern Germany, but she almost immediately sets out to visit her new property (after first struggling to locate it on a map), with her sister-in-law Susie, her niece Letty, and her niece’s governess in tow.

Anna does not get off to the best of starts with many of the locals, having absolutely no understanding of local customs or social hierarchies, but quickly falls in love her new home. Feeling blessed by good fortune, she soon decides that the best way to use her home and her fortune would be to throw open her doors to distressed gentlewomen, to give them the rest and comfort and independence they long for but can never have when relying on relatives or, if without family, scrambling to make a living. It is a beautiful, noble plan, though highly impractical as everyone tells her, and it isn’t long before Anna starts to regret her generous impulse, which has created an exhausting amount of work and stress for her.

While there are certainly more than enough of von Arnim’s trademark speeches about the tyranny of men and woman’s desire for and right to independence, this book actually has a male hero – not something typical in her works. Axel Lohm is the only other major landowner in the region and the only gentleman, too (something Anna recognizes with relief the first time she sees him, having exhausted her patience with crass peasants). He is the steady, good German gentleman Uncle Joachim had dreamed Anna might marry, a bachelor in his early thirties who has been devotedly attending to his estate, having bought his siblings out after their father’s death. For years, he has been doing his best on his own, but it is a lonely life for an intelligent, thoughtful man, whose family members can always think of something they would rather be doing than visiting him, or, if they do find themselves visiting, do their best to get away quickly. When Anna arrives, beautiful, warm, kind, intelligent Anna, they quickly become friends and it is not long before he falls in love with her, though he does his best to repress his feelings knowing that she does not welcome them. All of Anna’s affection and energy is to be devoted to her distressed gentlewomen, not to some man.

Axel is my favourite type of male hero – quiet, calm, responsible, stable – and my sympathies were all with him as he struggled to counsel Anna on her project, though in her enthusiasm she refuses to listen to any warnings, and then to conceal his love for her, knowing that any offer he made would be rejected. Anna dreamt for years of the kind of independence Axel has, but they were just that – dreams. In Axel, we glimpse the weighty reality of such independence and his acute loneliness. He has the freedom Anna always longed for but that alone cannot make him happy. It is only as Anna’s troubles begin to pile up that she starts to recognize that absolute independence is very isolating and very, very tiring. She has no one to share her burdens with, no one to help her see the way through a particularly overwhelming situation. She finally realises the limits of her much longed for independence: ‘I want someone to tell me what I ought to do, and to see that I do it. Besides petting me. I long and long sometimes to be petted.’

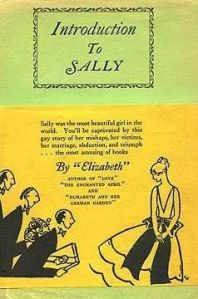

It is a surprisingly eventful novel, full of many comings and goings, and von Arnim indulges in an extravagantly dramatic final act that felt a bit jarring in comparison to what I think of as her typical style. I am used to thinking of her as a cool, humourous, unemotional storyteller, the writer of novels where the comic foibles of all the characters, major and minor, are exploited to excellent effect. (That reminds me that I still owe you a review of Introduction to Sally, which is riotously funny.) This is undoubtedly the least comic of her books that I have yet to read, which I think makes it particularly interesting and no less satisfying. It is still amusing – von Arnim could never be anything but – and quite light, but in showing an unusual amount of respect for her characters she creates a very different reading experience. Usually, I come away from my encounters with von Arnim impressed by her skill, thankful for her neat turn of phrase and gift for capturing and relating the ridiculous. Never before have I finished one of her books caring so much about the characters, as I did for the genuinely sympathetic Anna and Axel.

Read Full Post »

Today is the anniversary of Elizabeth von Arnim’s birth and in honour of that Jane is hosting Elizabeth von Arnim Day. I wasn’t quite organized enough this year to read and review something but she is one of my very favourite authors so I could not let the day go unmarked. Therefore, I thought I’d share the von Arnim’s I have read and reviewed over the years. They are, of course, ranked in order of preference from least favourite to most beloved. Enjoy!

Today is the anniversary of Elizabeth von Arnim’s birth and in honour of that Jane is hosting Elizabeth von Arnim Day. I wasn’t quite organized enough this year to read and review something but she is one of my very favourite authors so I could not let the day go unmarked. Therefore, I thought I’d share the von Arnim’s I have read and reviewed over the years. They are, of course, ranked in order of preference from least favourite to most beloved. Enjoy!

Like all of the Elizabeth books, The Adventures of Elizabeth in Rügen is exactly what you would expect it to be based on the title (much like

Like all of the Elizabeth books, The Adventures of Elizabeth in Rügen is exactly what you would expect it to be based on the title (much like

For years, my favourite of Elizabeth von Arnim’s novels has been

For years, my favourite of Elizabeth von Arnim’s novels has been